Resisting Obsolescence / A Model for an Indian Learning Center

2023 / Ahmedabad, India

Text 1

To resist obsolescence in architecture, it is necessary to examine the specific ways in which building culture and forms are inflexible and unresponsive to both the natural climate and our increasingly rapidly changing society. Because buildings take so long to design and build relative to changes in cultural and functional demands, they should anticipate changes that will happen far beyond their initial time and space. This project explores what it might mean to for architecture to return to its regionally specific sensibilities while simultaneously shedding the predetermined programs that centuries of building practices have mandated.

Text 2

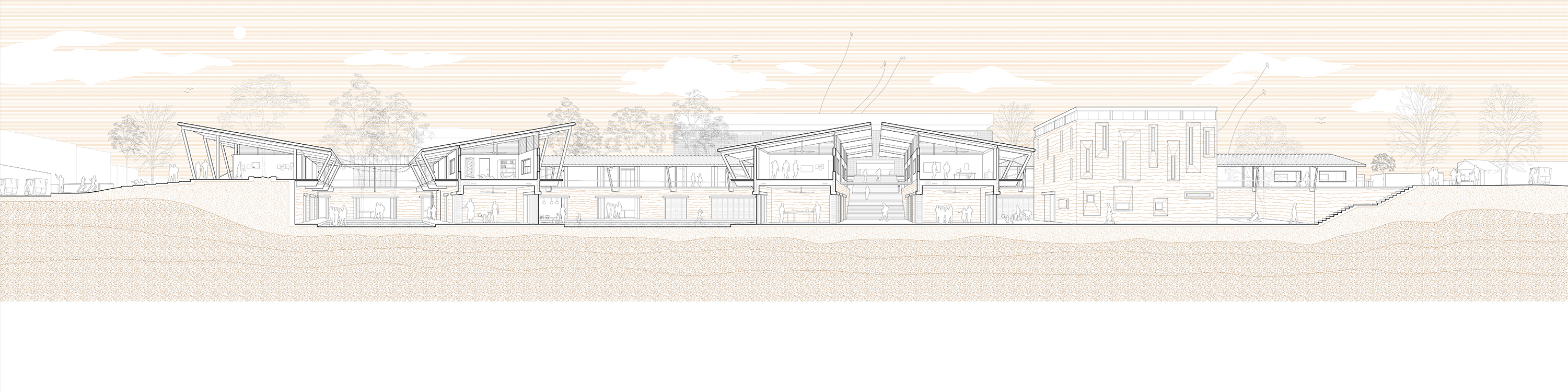

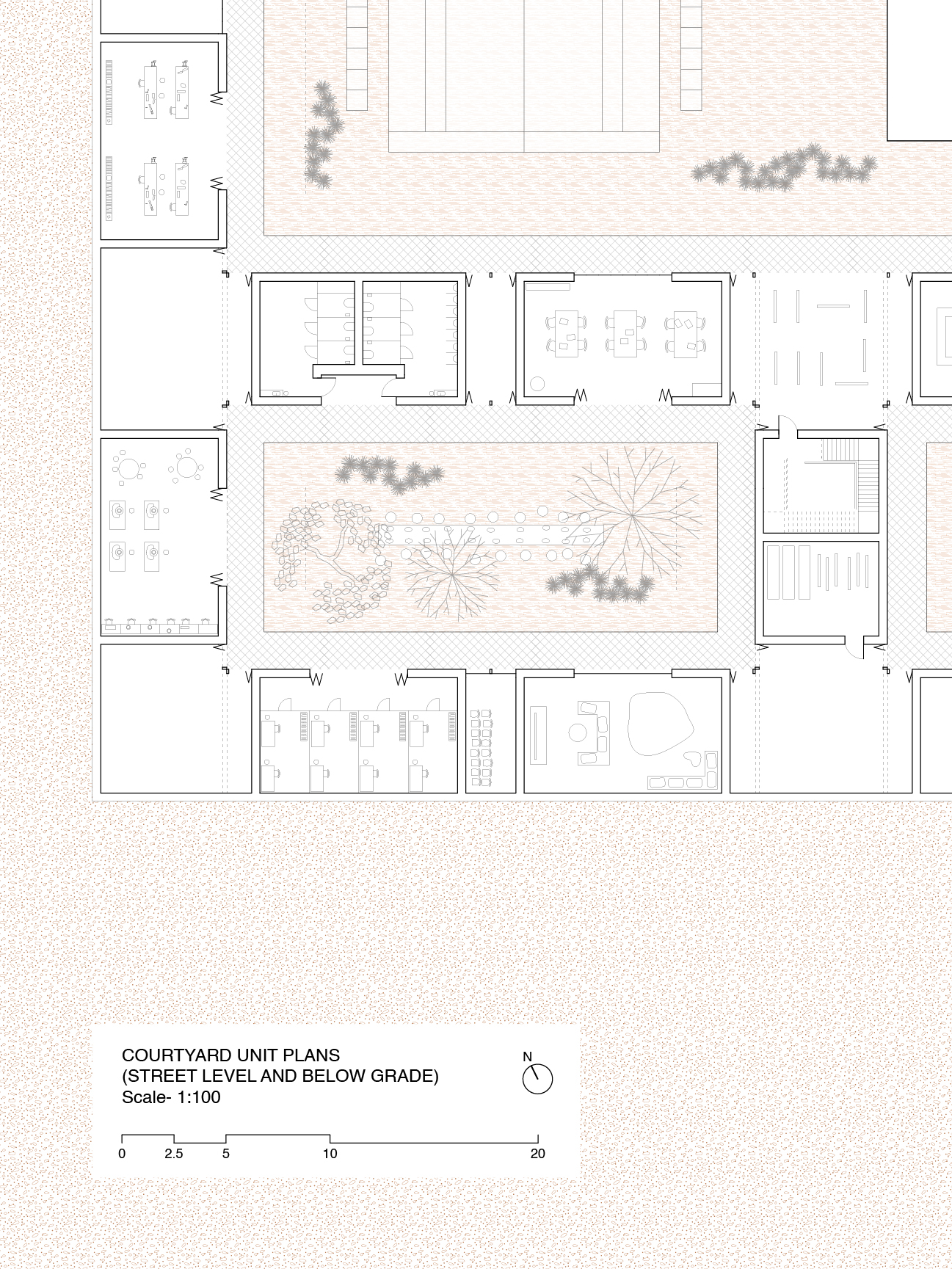

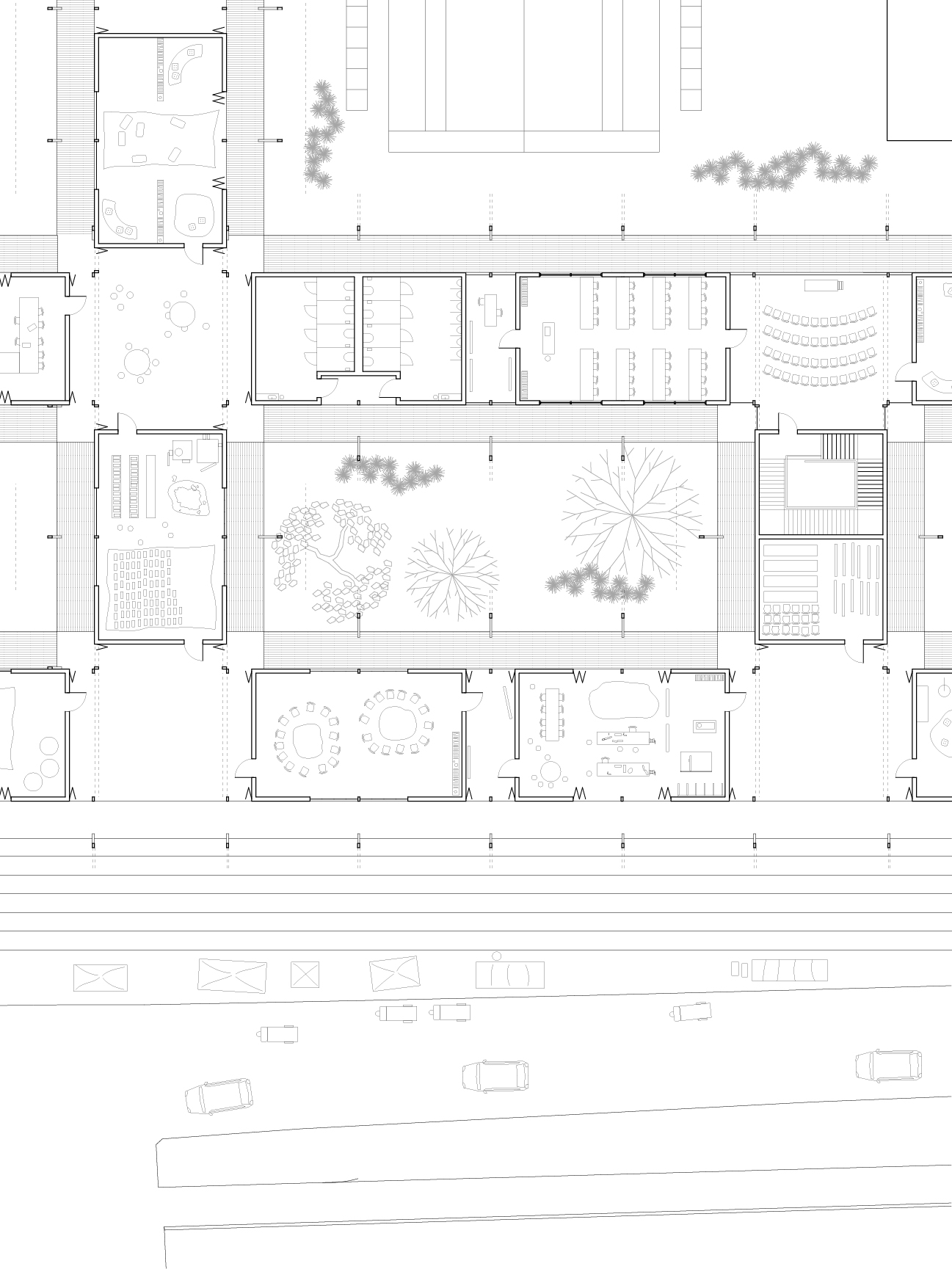

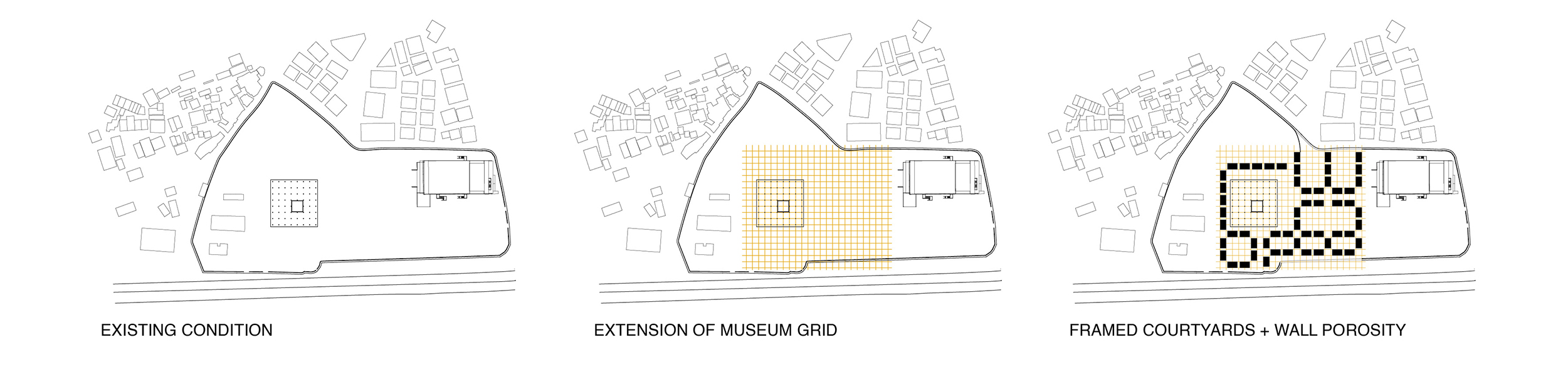

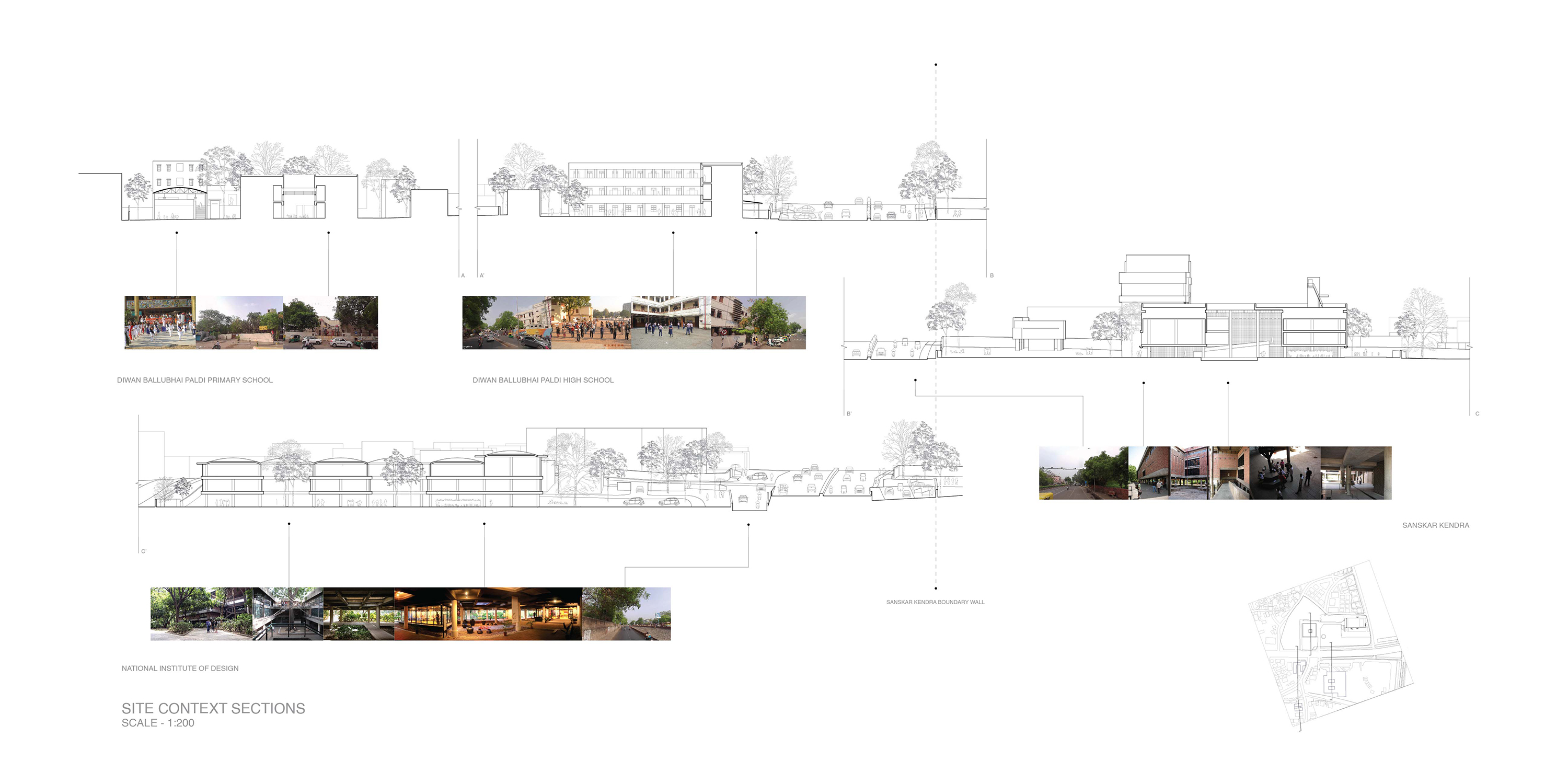

Analysis of surroundings found that in addition to NID, a primary and high school are both nearby, which together with the site’s lack of compelling purpose generated the core idea of the project: a flexible learning center for multiple levels and subjects of study which could provide amenities missing from each school. The site’s existing buildings and a series of new supportive ones are stitched together into a multivalent campus. Le Corbusier conceived the Endless Museum, and Sanskar Kendra by extension, as a static repository for cultural artifacts; this proposal reimagines it as a living participant in Ahmedabad’s urbanism.

Adopting the ideas of Structuralist architects like Herman Hertzberger, the formal strategy of the campus relies on a grid derived from Sanskar Kendra’s columns that hosts a network of volumes whose proportions and relationships suggest a diverse variety of uses. While individual units serve static functions like bathrooms, stairs and storage, others can be adopted as classrooms or workshops, their arrangement into village-like courtyards facilitating fluid transition to larger gatherings like sports games and performances. On a broader scale, this “loose-fit” nature permits part or all of the scheme to transform entirely into a Sunday market or other transitory space if needed. Volumes at the grid’s perimeter further emphasize the project’s concept as a city within the city by dissolving the site’s uninviting border wall, encouraging cultural exchange between Ahmedabad and the campus. The resultant complex functions less as a collection of individual buildings and more as a scaffold for daily life, one which can accommodate both changing day-to-day needs and longer-term shifts in programmatic requirements.